Discover Malta's

maritime history

etched in stone

Located at a crossroads in the central Mediterranean, the Maltese Islands have experienced the comings and goings of many different cultures and societies over time, reflected in a diverse and rich archaeological record. Graffiti from various periods of Maltese history are present on the island, from ship graffiti on prehistoric megalithic structures to aircraft depictions of the mid-20th century on chapels.

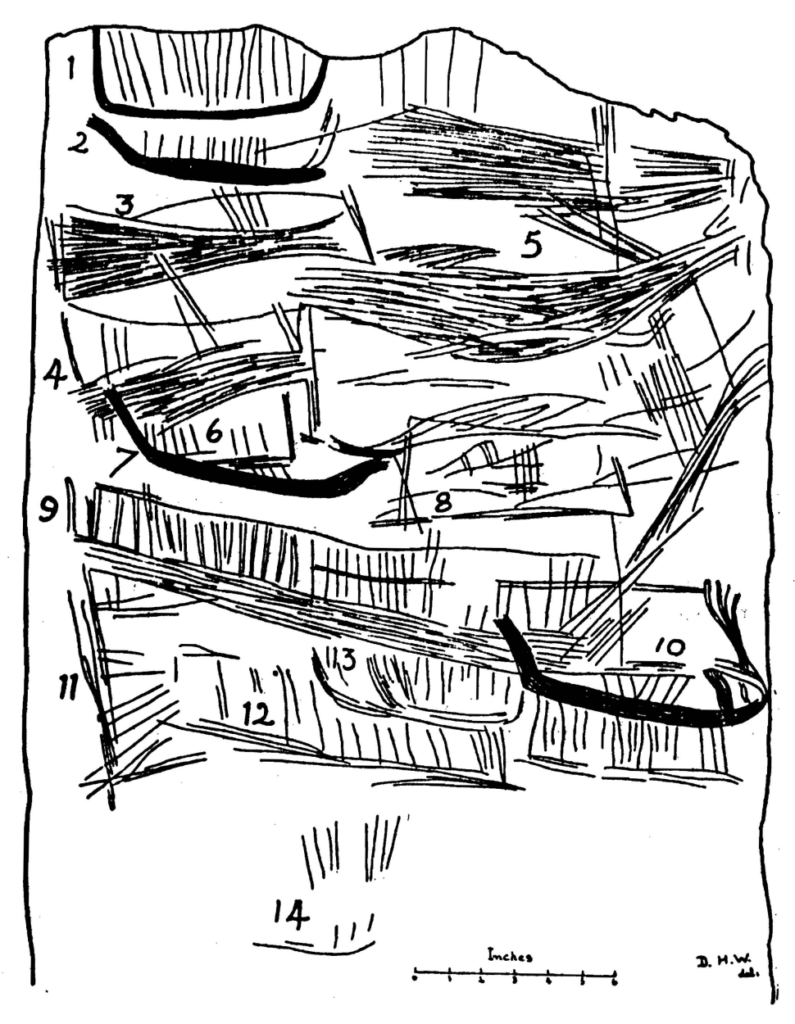

Prehistoric Malta saw the construction of megalithic structures, such as the Tarxien, Mnajdra and Hagar Qim temples. In the Tarxien megalithic complex, evidence of early maritime mobility is depicted through ship graffiti (see Woolner, D. 1957. Graffiti of Ships at Tarxien, Malta, Antiquity, XXXI: 60-68).

Being inhabited by Phoenician colonies then subsequently falling under Roman rule, the Islands were subjected to intense commercial maritime activities. Harbour activity intensified as ships from further distances reached the Maltese Islands either to seek refuge, to use the Islands’ amenities or to engage in commerce.

During the Byzantine period, a system of catacombs were hewn out of bedrock to serve as tombs. Interestingly, in both the Saint Paul and Abbatija tad-Dejr catacombs at Rabat, a number of ship graffiti have been discovered. One of the ship depictions has been identified as being possibly Roman in typology (Muscat 1934:57-61).

During this period, the Maltese Islands had an established Christian belief. This stance, together with Malta’s attractive geographical position in the Mediterranean, meant that the Islands’ political rule would be challenged yet again.

Read further:

Bonanno, A. 1991. Malta’s role in the Phoenician, Greek and Etruscan Trade in the Western Mediterranean, Melita Historica, 10(3): 209-224.

Gambin, T. 2012. A drop in the ocean – Malta’s trade in olive oil during the Roman period. In R. Abela (ed), The Żejtun Roman Villa: research – conservation – management: 86-97. Żejtun: Wirt iż-Żejtun.

Muscat, J. 1934. Il-Graffiti Marittimi Maltin, in M. Schiavone and C. Briffa (eds), Kullana Kulturali 2002, 36. Malta: Pubblikazzjonijiet Indipendenza.

Owing to the conflict between the Byzantine Empire and the ever-expanding Islamic influence of power, the Islands suffered multiple Muslim attacks which resulted in another political change. This political shift was accompanied by a change in language, lifestyle and religion for many of the inhabitants. Domestic dwellings and irrigation methods used in Malta and Gozo at the time reflect the occupants’ way of life.

In 1091, the Norman Conquest of the islands was successful. This resulted in Roman Catholicism replacing Islam as the religious status of the Islands. The Islamic influence over the inhabitants’ way of life survived despite the new rule.

Read further:

Dalli, C. 2004. ‘Greek’, ‘Arab’ and ‘Norman’ conquests in the making of Malteses history, Storja 2003-2004: 9-20.

The Islands were entrusted to the Order of Saint John by the Kingdom of Sicily in 1530. Considered a maritime power, the Knights Hospitaller are renowned for the effectiveness of their fleet of ships. Malta was designated to offer medical aid as a hospital for those pilgrims fighting for Christianity in Europe. Warring with the Ottoman Empire, the Order was prepared for a siege. Bastions and fortresses were erected in Malta and Gozo in order to protect the islands and the harbour areas were especially well guarded. This period also brought intense commercial and maritime activity to the Islands. Evidence of which is reflected in the wide array of graffiti etched into the walls of cities and villages.

Read further:

Abela, J and Buttigieg, E. 2018. The island order state on Malta, and its harbour c.1530 – c.1624. In C. Vassallo and S. Mercieca (eds), The Harbour of Malta: 49-74. Malta: Progress Press.

Gambin, T and Kassulke, M. 2023. Maritimity in Stone: An Archaeology of Early Modern and Modern Ship Graffiti in the Maltese Islands (ca. 1530 – 1945), Historical Archaeology, 57(1): 1162 – 1176.

In 1798, the islands fell under attack from Napoleonic forces, resulting in the expulsion of the Order of Saint John. In 1800, the Islands became a British protectorate, and part of a vast maritime empire that used the sea as a medium for transport of goods and people.

Read further:

Clare, A.G. 1981. Features of an island economy: Malta 1800 – 1914. Hyphen, 2(6): 235-255.

Under British rule, the Maltese islands were subject to unrelenting attack in World War II. Harbour cities were under the constant threat of air raids forcing the local population to migrate to safer villages. During the war period, food and supplies became increasingly scarce. The effect of the war on the local population is still remembered on symbolic days such as the Feast of the Assumption, celebrated on 15 August. On the day of the feast, a convoy entered the Maltese Islands after many failed previous attempts, restocking the Islands with desperately needed supplies. Graffiti from this period are a common find on the Islands.

Read further:

Cassar, G.N. 1967. Gozo during World War II. In B. HIllary (ed), The Malta Yearbook 1967: 304-315. Malta: St. Michael’s College Publications.

Caruana, J. 1992. The Malta Convoys of 1942. In S. J. A. Clews (ed), The Malta Year Book 1992: 437-441. Malta: De La Salle Brothers Publications.

Surviving the war, the Maltese Islands went through a post-war recovery period where some of the damaged buildings were rebuilt. Slowly but surely, the Islands’ inhabitants realised a new normal in their everyday living. Malta’s economy slowly regained strength and the native population started rearing for a local government, autonomous from the British. Ultimately, in 1964, the Maltese islands achieved independence following the Malta Independence Act.

Read further:

Pullicino, J. 2017. Malta’s reconstruction after 1945. University of Malta: B.A. (Hons) History. Dissertation.